“The Argument,” a short film directed by Donald Cammell and edited by Frank Mazzola, is an experimental piece that was filmed in 1971 but remained unfinished until 1999. The film centers on an intense and enigmatic dialogue between two characters, a man and a woman, whose identities and relationships remain deliberately ambiguous. Set within the surreal landscape of Utah’s desert, the couple’s conversation oscillates between philosophical musings and personal grievances, creating a tense and introspective atmosphere.

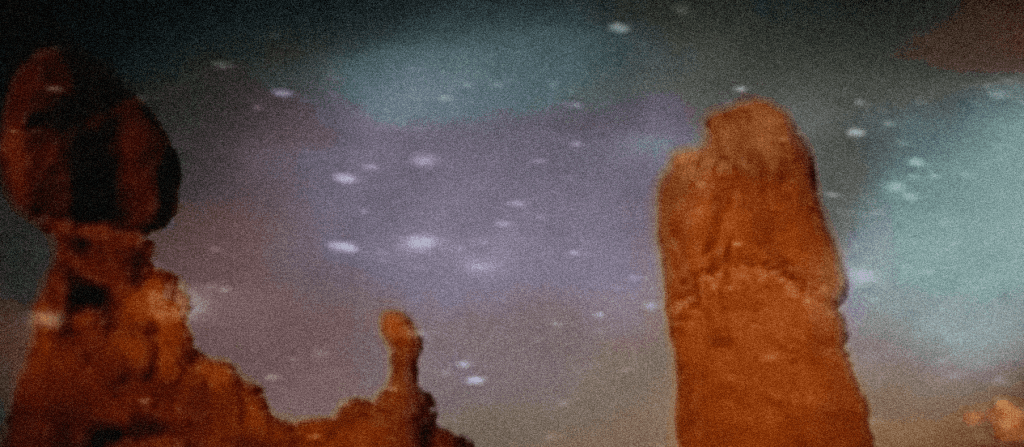

Through fragmented narrative and evocative visuals, Cammell and Mazzola explore themes of reality, perception, and the nature of human connection.

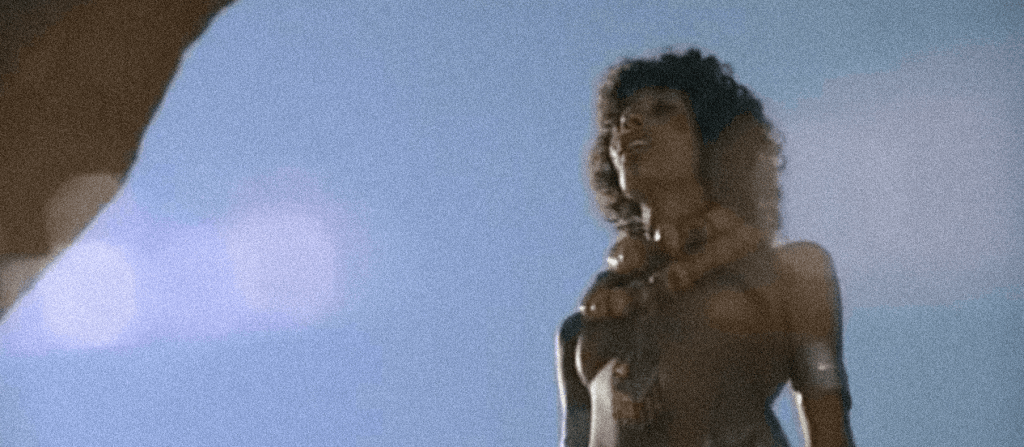

The film was shot in Bryce Canyon by the renowned cinematographer Vilmos Zsigmond. It is a visually stunning piece. The cast includes Myriam Gibril as Aisha the Witch and Kendrew Lascelles as the Director.

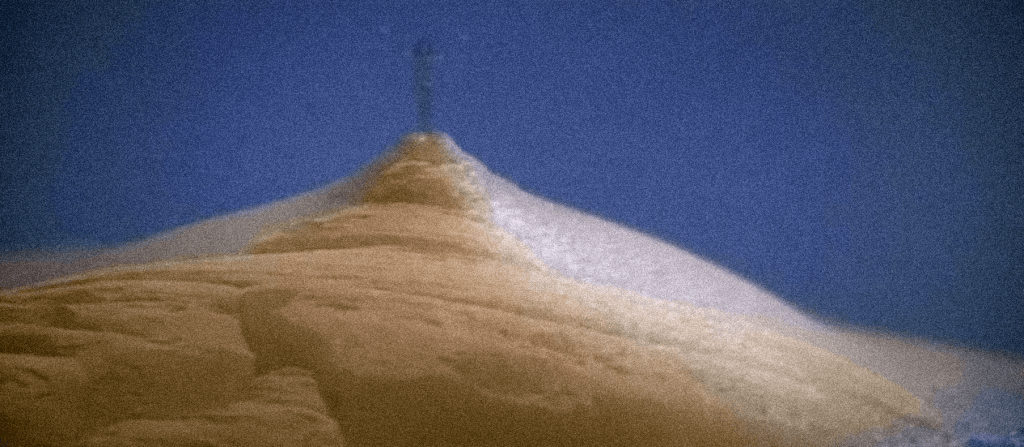

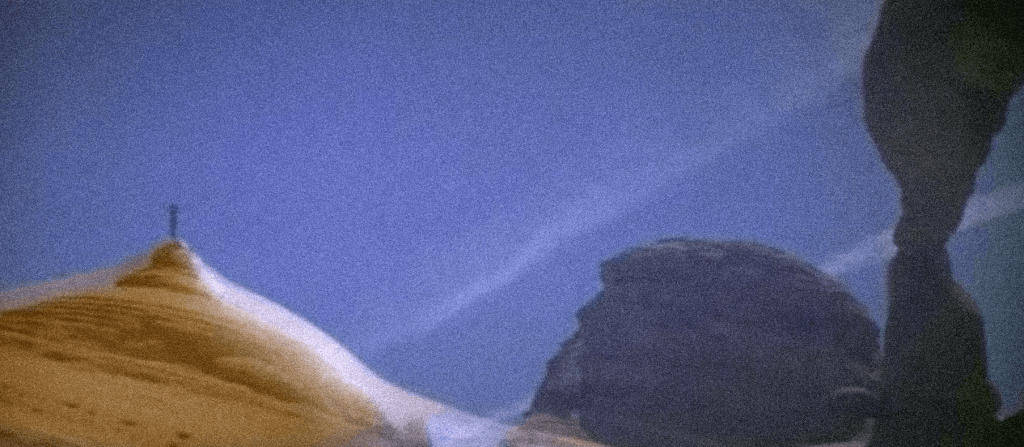

The film starts out with striking sweeping landscapes as a character off-screen warns the director of how temperamental a goddess can be, to which he rebukes and informs us and the character that he will take care of it and that it’s his film and he is the director. We hear Aisha announce from afar that she is Aisha, the witch. She then questions if the film crew has a god, to which one whispers to the other. Did she say, “If he has one, is that what she said?” She replies immediately, “That’s exactly what I said.” We then hear someone say, “That’s not in the script.” More importantly, we’ve established the premise for the argument: a battle of the sexes, a clash of philosophies, and personal beliefs—all presented in a very ambiguous way. It can be seen as an observation of reality or perhaps something deeper..

The film is established as a back-and-forth between the two characters as the director makes statements such as “his” purpose, and she questions it with why not “her” purpose. In these moments, Cammel uses his signature surrealism pioneered during the editing of ‘Performance,” where the rock formation, the witch stands one, dissolves into a woman’s breast.

The director suddenly finds himself alone, calling out to the rest of the crew, who are nowhere to be found. He wanders around the majestic landscape and walks into a darkened area, thinking he is beyond the shadow of the Valley of Death. He then comes across the witch again and complains that she is taking liberties with the script. She announces that she is merely improvising, much to the annoyance of the director, who again uses “he” as a pronoun when referring to the creation of the earth. She accuses him of being sexist, and when he tries to counter, she shouts “Fuck you” at him, and suddenly the script that he has been carrying disappears as if being instantly punished for his thoughts. The film then goes into a trippy psychedelic sequence as if projecting the witch’s powers. During this time, the director demands his script back. He then tries to reason with Aishsa by proclaiming god is man.

As the sequence gets more surreal, it begins to dissolve in historical footage of Nazis and the atomic bomb, all products of man. As the sequence closes, we slowly zoom in on the now naked director, who proclaims that he has “given up” and that they have to resolve their conflict. The film comes to a close as it is clear that the director will never see an opposite point of view. He then mutters, “For God’s sake,” at which Aisha announces, “For my sake,” and decides to resign. From the film? Or from him? That is the question.