‘Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom,’ is a 1975 controversial and highly provocative film directed by Pier Paolo Pasolini. Based loosely on the infamous novel “The 120 Days of Sodom” by the Marquis de Sade, the film is a brutal allegory about power, sadism, and the dehumanizing effects of totalitarianism. Set in Fascist Italy during the final days of World War II, the film explores the moral degradation and violence inflicted by authority figures on the helpless, using extreme and disturbing imagery to make its point.

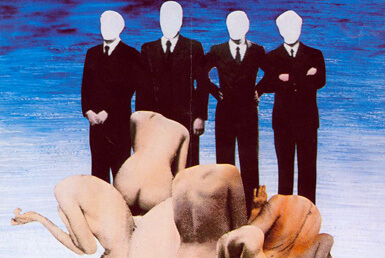

The film takes place in the Republic of Salò, a puppet state established by Mussolini in northern Italy in 1943-1945. Four wealthy and corrupt libertines—known only by their titles: The Duke (played by Paolo Bonacelli), The Bishop (played by Giorgio Cataldi), The Magistrate (played by Umberto Paolo Quintavalle), and The President (played by Aldo Valletti)—collaborate to enact a horrifying series of sadistic rituals and abuse on a group of abducted young men and women.

The libertines, who represent the extreme abuses of power by fascist and authoritarian regimes, kidnap eighteen teenagers (nine boys and nine girls) and imprison them in a secluded villa. Over 120 days, they subject their captives to escalating forms of physical, sexual, and psychological torture. The film is divided into four distinct sections, corresponding to Dante’s structure in “The Divine Comedy”:

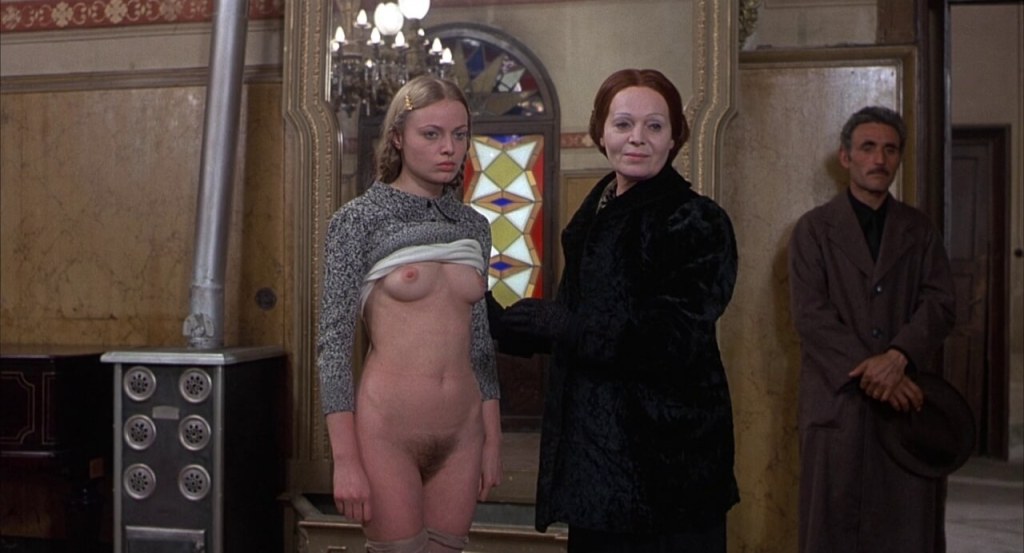

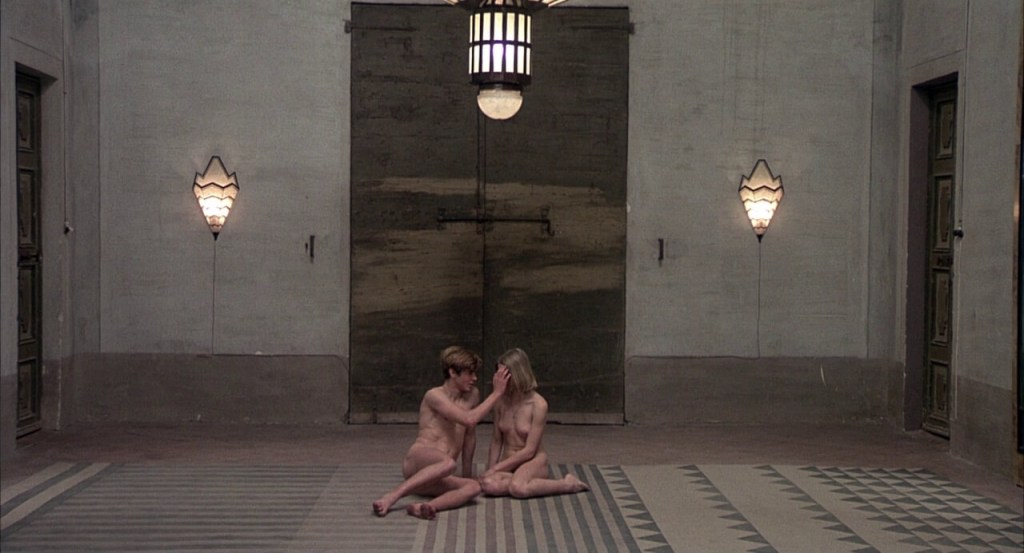

Antechamber of Hell: The libertines gather their victims and prepare them for what is to come. The teenagers are stripped of their identities and reduced to mere objects for the libertines’ pleasure and cruelty.

The Circle of Manias: In this section, one of the libertines’ accomplices—older women known as storytellers—recounts sexually depraved stories while the libertines force the captives to reenact the perversions described. This section begins the dehumanization of the victims as they are forced into grotesque acts of humiliation and degradation.

The Circle of Shit: The libertines escalate their sadistic cruelty, forcing the captives into acts of extreme degradation, including forcing them to consume human feces. This segment represents the libertines’ ultimate contempt for human dignity and morality.

And finally, The Circle of Blood: The final section that reaches the peak of sadistic violence, where the libertines engage in increasingly horrific and violent acts of torture. As the captives are murdered one by one, the libertines observe the atrocities with detached voyeurism, reinforcing their absolute control and domination over their victims.

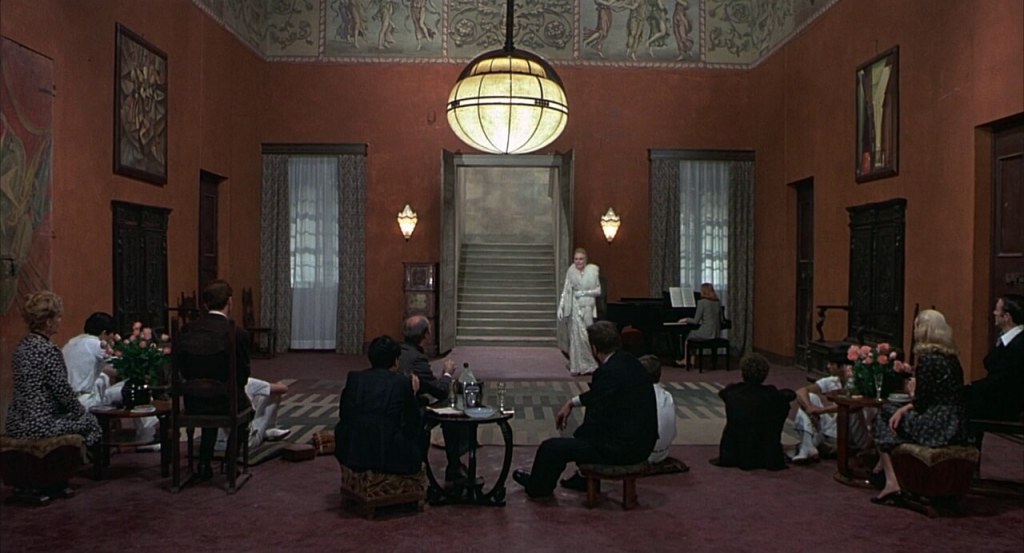

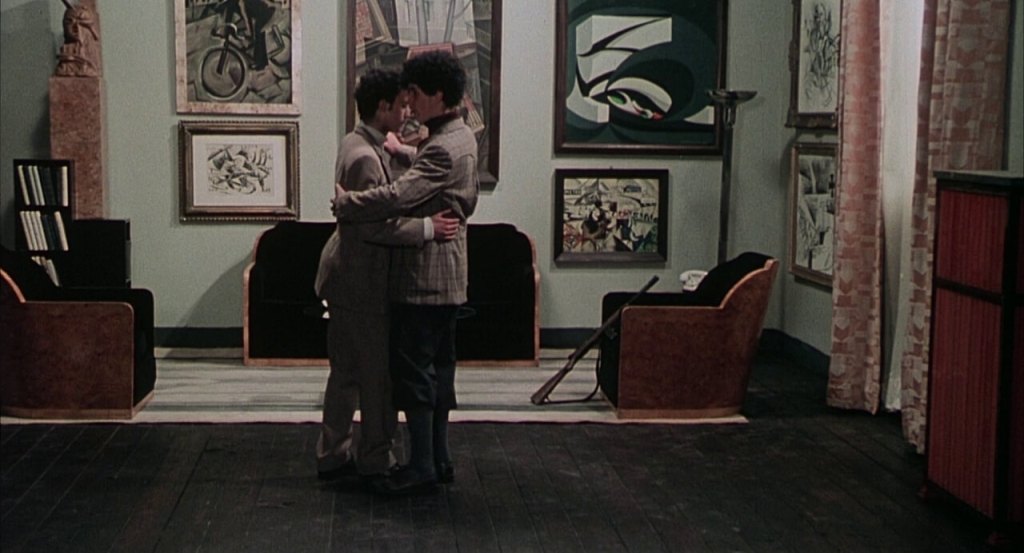

Throughout the film, the libertines are shown reveling in their sadism and the complete submission of their captives. They hold lavish banquets, listen to classical music, and engage in philosophical discussions about power and depravity, juxtaposing their cultured exteriors with the horrors they inflict. Meanwhile, the young captives are left to suffer in silence, trapped in a cycle of torture that strips them of all humanity.

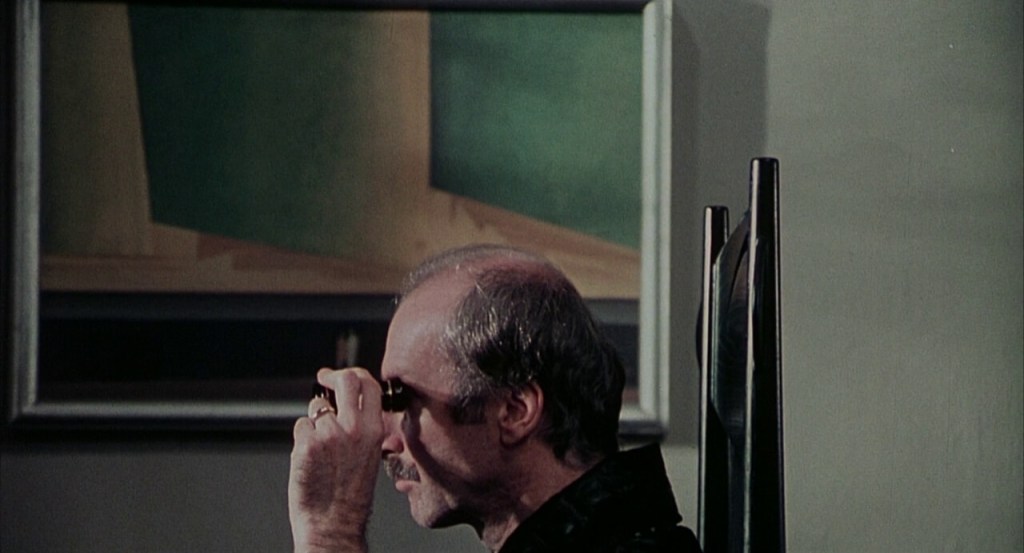

In the film’s final scenes, the libertines watch through binoculars as their guards enact brutal executions on the remaining captives. The libertines’ cold detachment emphasizes the banality of evil and the systemic cruelty inherent in totalitarian regimes. The film ends with two of the libertines’ guards engaging in a banal conversation about dance steps, underscoring the chilling normalcy of their surroundings in contrast to the horrors they have just witnessed.

“Salò” is widely regarded as one of the most disturbing films ever made, not only for its graphic depictions of sexual violence and bodily mutilation but for its unflinching portrayal of the degradation of the human spirit under oppressive regimes. Pasolini intended the film as a political allegory, condemning the dehumanizing effects of fascism, capitalism, and authoritarianism. The libertines’ perversions and their total control over their victims represent the unchecked power of the state and the moral decay that comes with it.

The film’s stark, clinical style reflects its brutal content. Pasolini uses static shots and long takes, creating a cold, detached atmosphere that forces the audience to confront the horrors on screen without the emotional distancing that more conventional film editing techniques can offer. The luxurious villa setting contrasts with the grotesque acts committed within, symbolizing the way authoritarian regimes cloak violence and oppression in the guise of order and civility.

Pasolini’s decision to adapt the Marquis de Sade’s novel and set it in Fascist Italy was not coincidental. He sought to draw parallels between de Sade’s philosophy of absolute freedom and the totalitarian regimes of the 20th century, particularly Fascism and Nazism. The libertines in the film exercise total control over their captives, embodying de Sade’s idea of freedom without limits, where morality is irrelevant and power is the only guiding principle.

“Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom,” remains a deeply polarizing film. Upon its release, it was banned in several countries for its explicit content. However, it has since been revisited as a powerful critique of political corruption, abuse of power, and the horrors of fascism. The director, Pier Paolo Pasolini, was murdered shortly before the film’s release.