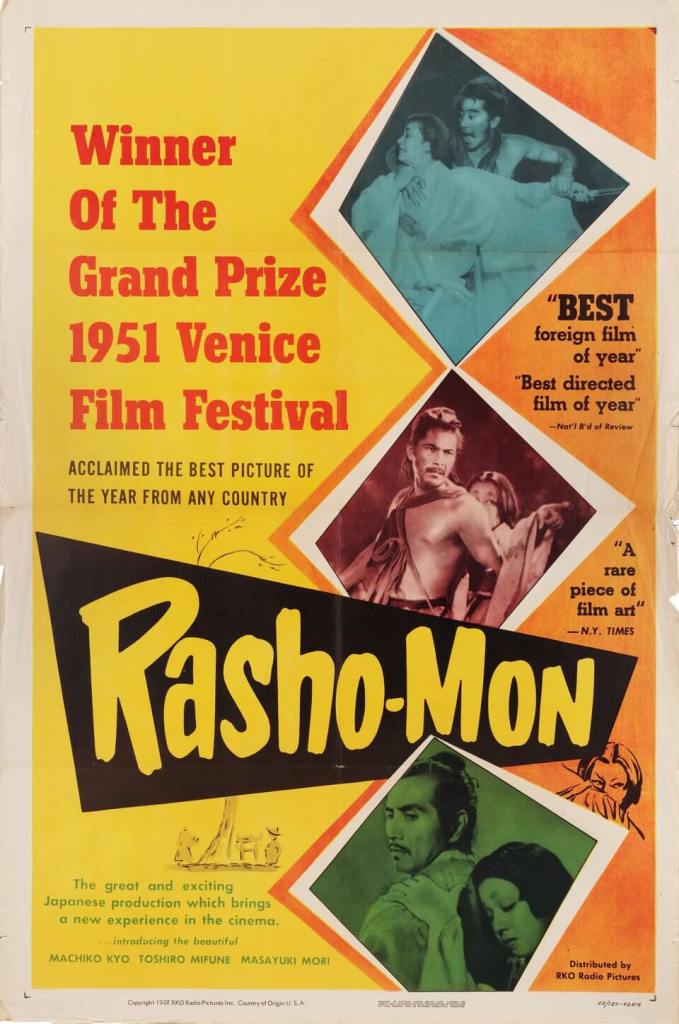

Rashomon (1950), directed by Akira Kurosawa, is a groundbreaking Japanese film that delves into the subjective nature of truth and the complexity of human perception. Starring Toshiro Mifune, Machiko Kyo, Masayuki Mori, and Takashi Shimura, the film presents multiple contradictory accounts of a violent crime, leaving audiences to question the reliability of memory and the concept of objective reality.

The film opens on a desolate, rain-drenched gate, Rashomon, where three men—a woodcutter (Takashi Shimura), a priest (Minoru Chiaki), and a commoner (Kichijiro Ueda)—seek shelter. The woodcutter and the priest, disturbed by a recent event they witnessed, recount the story to the commoner. This story centers on the murder of a samurai (Masayuki Mori) and the assault of his wife (Machiko Kyo) in a forest. What follows are four different perspectives on what happened, each story recounted by a different participant in the crime.

In the first account, given by a notorious bandit named Tajomaru (played by Toshiro Mifune), he admits to murdering the samurai and boasts of his cunning and skill. Tajomaru claims he was captivated by the samurai’s beautiful wife and lured them into the forest. He recounts seducing the wife, who then, according to him, encouraged him to duel her husband to prove his strength. Tajomaru’s story paints him as a swashbuckling villain who proudly defeated the samurai in combat.

The wife’s account, however, presents a different picture. Humiliated and traumatized by the assault, she claims her husband looked at her with disdain afterward. Feeling rejected, she describes a scene where she begged him to forgive her, only for him to remain cold and unmoved. In her version, she admits to stabbing her husband in a fit of despair, but she portrays herself as a victim of circumstance driven by shame and desperation.

Then, through a medium, the dead samurai offers his testimony from beyond the grave. His version contradicts both Tajomaru’s and his wife’s accounts. He claims his wife, after the assault, begged Tajomaru to kill him, viewing her husband as weak and pathetic. The samurai, ashamed and dishonored, recounts taking his own life with a dagger after Tajomaru abandoned him. This spectral account adds a surreal layer to the narrative and casts doubt on the previous stories.

The final version is provided by the woodcutter, who initially claimed to have only stumbled upon the body but now reveals that he witnessed the entire incident. In his account, neither the samurai nor Tajomaru appeared particularly brave or noble; instead, both men fought clumsily and reluctantly, and the samurai was killed not in a glorious duel but in a scuffle that seemed petty and ignoble. This version exposes the self-serving motives underlying each character’s story and suggests that all are guilty of exaggerating or altering the truth to suit their own narratives.

As the men at Rashomon Gate struggle to make sense of the conflicting testimonies, the woodcutter discovers an abandoned baby. This unexpected moment of vulnerability and compassion brings a sense of redemption. The woodcutter offers to take the baby home, and his gesture renews the priest’s faith in humanity, suggesting that despite lies and moral ambiguity, there is still potential for goodness.

Rashomon revolutionized cinematic storytelling with its innovative narrative structure and exploration of subjective truth. The film’s visual style, especially Kurosawa’s use of light, shadow, and natural elements, enhances its themes and the performances—particularly Mifune’s wild, charismatic portrayal of Tajomaru and Kyo’s layered, tragic depiction of the samurai’s wife—give the film emotional depth.