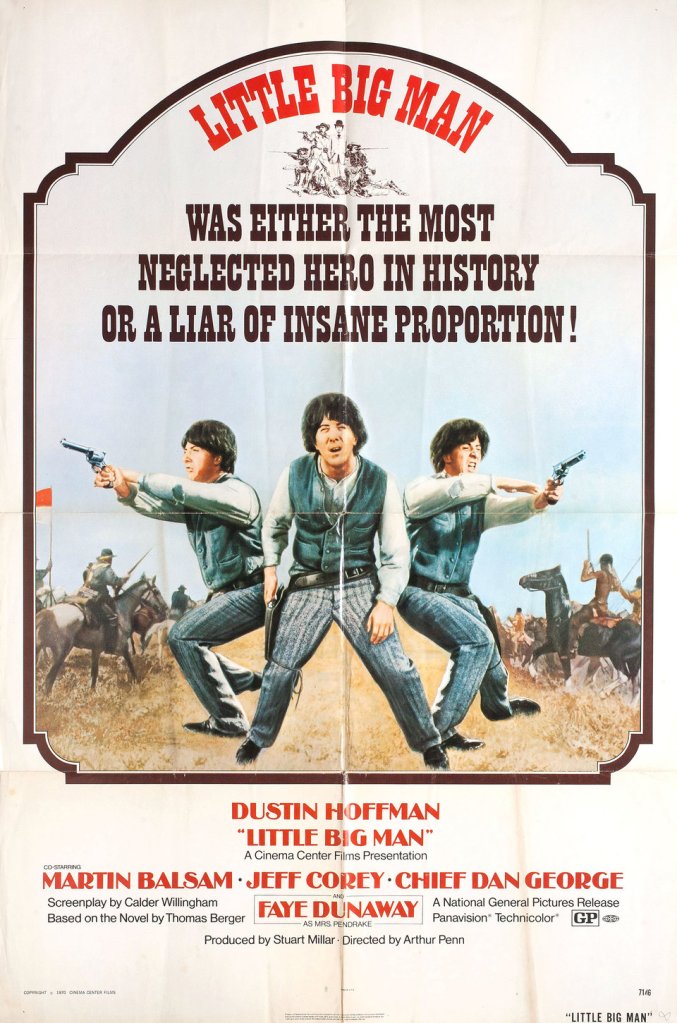

“Little Big Man,” a 1970 film directed by Arthur Penn and based on the novel by Thomas Berger, is a revisionist Western epic that blends satire, tragedy, and historical fiction. It tells the story of a 121-year-old man named Jack Crabb (Dustin Hoffman) as he recounts his incredible life journey through a series of flashbacks. The film offers a scathing critique of the traditional mythology of the American West, particularly the U.S. government’s treatment of Native Americans.

It opens in the 1970s, where a researcher interviews Jack Crabb in a retirement home. Jack claims to be the only white survivor of the Battle of the Little Bighorn, and from there, he begins narrating his sprawling, picaresque life story.

As a young boy in the mid-1800s, Jack and his sister Caroline are orphaned when their family is killed by Pawnee raiders. Soon after, Jack is adopted by the Cheyenne tribe, where he is lovingly raised by Old Lodge Skins (Chief Dan George), a wise and peaceful tribal elder who sees Jack as “Little Big Man” for his bravery and small size.

Jack grows up immersed in Cheyenne culture, identifying with their values of harmony and community. However, his life takes repeated turns as he is captured by white settlers, “rescued” by missionaries, becomes a snake oil salesman, and is then manipulated by General George Armstrong Custer (played with comic madness by Richard Mulligan). Each stage of his life exposes him to a different facet of 19th-century American society, from the corrupt clergy and violent settlers to racist soldiers and opportunistic businessmen.

One of the more memorable episodes involves Jack becoming the lover of Mrs. Pendrake (Faye Dunaway), a hypocritical minister’s wife who espouses virtue but harbors deep sexual repression. He also works as a gunslinger and crosses paths with Wild Bill Hickok (Jeff Corey), witnessing the violent absurdities of frontier justice.

Despite his many identities—white boy, Cheyenne warrior, gunfighter, and conman—Jack always finds himself torn between two worlds: the brutal expansionism of white America and the dignified, if doomed, life of the Cheyenne people. His emotional and cultural allegiance remains with the Cheyenne, especially after falling in love with Sunshine (Aimée Eccles), a Cheyenne woman who becomes his wife.

Tragedy strikes when U.S. soldiers massacre a peaceful Cheyenne village in a scene reminiscent of the Sand Creek Massacre. Sunshine, pregnant with Jack’s child, is among the victims. The brutality of the slaughter crystallizes Jack’s hatred for Custer and the U.S. military’s genocidal policies.

The film’s climax comes at the Battle of the Little Bighorn in 1876. Jack, having rejoined Custer’s unit under false pretenses, witnesses the general’s arrogant leadership lead his troops to total destruction at the hands of the Native American coalition. Jack survives the battle and returns to Old Lodge Skins, who prepares for death with dignity and grace, only to find that he is not yet ready to die.

In the final scenes, an aged Jack Crabb reflects on losing a way of life, the folly of empire, and the senseless violence of the so-called “winning of the West.” Little Big Man is a satirical epic and a tragic deconstruction of the classic Western genre. It was one of the first major Hollywood films to present Native Americans sympathetically and with complexity, challenging long-standing stereotypes. The film illustrates how history is subjective, distorted, and often absurd. Through Jack’s shifting identities and the episodic structure.

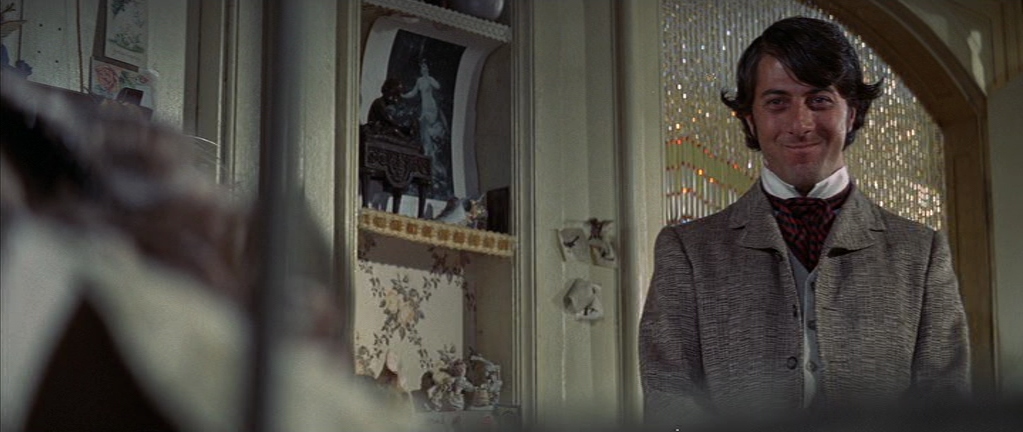

Dustin Hoffman’s performance, heavily made up to play an old man—noting that the godfather of make-up DIck Smith was helmed with the challenge of aging the then 32-year-old Hoffman and skillfully navigates decades of his character’s life—is central to the film’s emotional and comedic tone. Chief Dan George received an Academy Award nomination for Best Supporting Actor, delivering a performance of quiet wisdom and understated humor that earned widespread acclaim.

Director Arthur Penn, coming off the success of Bonnie and Clyde, uses the film to critique American exceptionalism and the myth of frontier heroism. The film mixes comic, tragic, farcical, and solemn, emphasizing American history’s chaotic and contradictory nature.